The Last Mile II

Never Bank on the Last Mile

What’s the first word that comes to mind when you see:

70-year-old couple

Holding hands

Completes marathon

LAST WEEK’S POST left you all in the lurch.1

I woke up that morning expecting to run a five-hour marathon yet found myself at the halfway point with 4:00:00 in my crosshairs.

But there’s a big difference between 13.1 and 26.2. A chasm that only blistered feet, aching knees, a screaming bladder, and a mind gyrating with negative self-talk.

There I was.

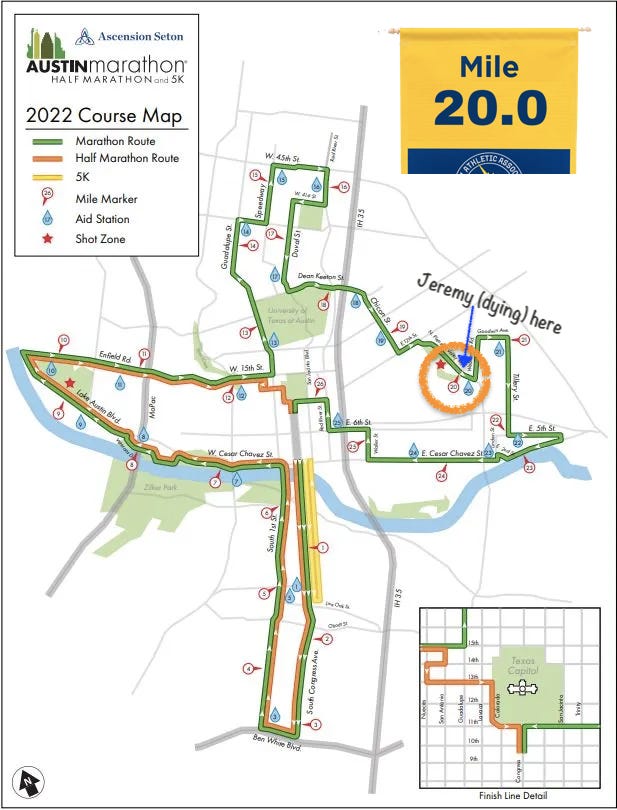

Mile 20: fingers frozen, legs like throbbing and chafing and joggling like jello, gut and bladder stabbing with cramps. Even worse—the doubt, the apathy, the self-pity.

My pace had slowed to ten minutes per mile, which put me far outside the 4-hour marker I was hunting

And then, wallowing in shame, I saw the best thing I’ve seen in a long, long time.

Left: A 70-year-old woman with short brown hair and an orange vest that said “GUIDE”

Right: An even older man, clutching his wife’s elbow, in a matching orange vest which read “Visually impaired runner.”

Visually impaired runner.

We were on a sun-drenched straight away which curved slightly down hill and gave me a chance to use the hill and make up some time.

But I didn’t speed up, couldn’t. I found myself in a fugue—body carrying on, mind elsewhere.

I couldn’t take my eyes off the man’s block-lettered vest.

What could a blind older gentleman be running for? I wondered.

He couldn’t see the fans on the sides of the roads. Wouldn’t run home and post his time on social media2. Wasn’t using the smiles on his family’s face as fuel..

Only then I understood who he was running for.

Himself. Not to impress others. To impress himself.

A blade of sun slashed through the corner of my sunglasses and I was vaulted back into my own body and knew all at once that if I let myself lose sight of that four-hour setpiece, I would never get there, ever.

Buzzing underpasses, hilly parks, breweries.

At mile 23, the course leveled off to a straightaway down East Caesar Chavez.

With newfound motivation, I reeled my pace back in to 9 minutes 10 seconds—a just under 4:00:00 pace.

Cars and trucks rushed in and out of sight, mixing the scent of freshly brewed beer with that of of gasoline and hot rubber.

In front of CMW, the brewery had put out shots of OJ and after two hours of artificial enery gels and electrolyte drinks, the natural tangy smell of orange juice had my skin tingling.

All consideration of my surroundings had gone out the window as I ran diagonally toward the OJ. A thin man in a lime green tank top and Brooks and a backwards hat came out of nowhere. The collision was immediate and unavoidable. The moment stretched in the sort of slow-motion way that time dilates when you are about to catch an injury. My foot caved on a slight change in the pavement and my knee buckled inwardly. We both flailed and stumbled and must have looked like drunk teenagers at a rave. But neither of us fell. The guy growled and threw his hands in the air and sped off.

The amount of stumbly off balance steps I took could have been the sight of a cartoon. After four or five off balance paces I caught myself on the edge of the very last table and sort of bounced off it like some kind of sweaty pinball. I continued on a few paces, waiting for the shock to twist into pain.

I was lucky. It never did.

All that followed were aches in all the places that are familiar to runners and I just thought of the blind man running somewhere behind me, and the nice lady with the pacer flag from (part I).

I plowed from station to station gulping as much water as my swollen bladder could endure, repeating this mantra like some kind of a brain-dead poser-robot:

"This is what I work for. This is what I work for.”

It was bright now and the warmth that must have been nice for onlookers was thick as hell and fire in the lungs. We turned onto the East 6th Street downhill and I saw a sign for the last mile.

My watch read 3:52:00 minutes.

That meant eight minutes to run one mile.

—If you’ve seen me move you know I’m not very fast, not so strong.

But I am a good finisher.3

Eight minutes was 70 seconds faster than my pace on the previous 25 miles.

Yet, I knew that I could easily turn off my brain for eight minutes if it meant finishing in under 4 hours, meant being accepted in the ‘real runner’s club.’

I emerged from the sixth street downhill and highway underpass and found the crowd beginning to thicken.

My watch read ‘7:55/mile’

The road had started to slope upward but I charged through that incline at an 8 minutes 5 seconds pace.

I caught sight of a pretty girl in white and wondered how I must look: grimacing, gasping, salt stains up and down my shirt, orange juice on my arms, talking to myself, frantically firing my arms like an Olympic speed walker.

The crowd was loud now and people screamed and shook signs and waited with cameras for their runner friends to emerge.

3:58:00

There was a turn up ahead. I imagined myself making that final left and seeing the finish line a football field away and doing what I do best. Stepping on the gas at the last minute. Finishing strong, with seconds to spare.

I made the turn.

Last week I wrote about a few lessons the first 20 miles taught me.

But the lesson I learned in the final 6 is the one that will stick with me until I’m 70 and blind and running a marathon

Never. Ever. Bank on the last mile.

3:59:00

No finish line.

I found myself with just 60 seconds to climb what was far and away the steepest hill of the day. Fifteenth Street.

Lining the road up the hill on the curb was a mass of people. In them, I saw two facial expressions multiplied a thousandfold: violent pride and mesmerized fear. I made eye contact with a tall middle-aged gentleman who looked as though he may have done one of these before4. He shouted:

“You’re almost there!”5

3:59:30

I can just see the crest of the hill another 20 yards up, another 10 steps.

I reach the peak with five seconds left and there’s the finish line.

My finish line, the rows of roaring spectators and cameramen and race volunteers.

Five seconds left, my sweet finish line. . . still a football field away.

At that point my worst self (who you met in pt I) came raging back to life.

I'd missed my 4:00:00 mark.

No one would call me a “real runner,” so why not slow down?6Believe me, I was about to do it.

But then, by some stroke of psychic luck, the image of the blind man and his wife and the kind woman with the pacer flag came back, and I decided right then and there to not give one single fuck about not being considered a “real runner.” Decided that this moment of having the option to slow down and choosing the hard way instead was what I had worked for, trained for.

In the face of pain, to not slow down, to not consider what people think. To speed up. To impress the only one who mattered: myself.

I looked up at the finish line in the mid-distance and opened my stride and took down the final .2 miles at a 7:00/mile pace.

4:01:30

It’s easy to say in hindsight, but I’m actually glad I didn’t break four hours.

Imagine if I had. Imagine thatthe race-makers had programmed an easy final mile rather than a steep hill, and I had turned on the jets at just the right time to sail in with seconds on the clock.

Would I have learned the lesson?

Or would I have taken my “real runner” badge, “strong finisher” plaque, and “total d-bag” pin and continue through my late twenties and thirties and adulthood believing that it’s acceptable to procrastinate. Acceptable, because I would always somehow manage to make up the time in “the last mile,” as I’d done in the Marathon.

We’ve all heard someone claim that “failure is not an option.”

Failure is absolutely an option.

And an excellent one at that.

Coming that close and failing was so excruciating, so devastating to my ego that there is no chance in hell I will ever let something like that happen again.

In Meditations Marcus Aurelius7, one of the greatest leaders to ever live, challenges :

“Interrogate yourself. Find out what you are doing, what inhabits your so called mind, what kind of soul you have today.”

—Marcus Aurelius (V,11)

You can read my story and feel inspired and take it as a call to action—but I challenge you to take it as a call to self interrogation.

What is your bad habit that needs breaking?

What’s your ‘marathon’ that needs running?

Where are you banking on the last mile?

Thanks for reading, vaqueros!

If you enjoyed this post, please feel free to share my Substack with a friend who might be interested. And also! Comment or reply to this post - love hearing from you.

And if you happened to miss part one of this series, here is the link

The February Reading List coming soon…

Be good 🖖

—Jeremy

For that, I apologise

Or substack. . .

A deceptive ‘skill’ aka anti-skill aka skill-turned-flaw which I suspect is at least in part why I am either A) exactly on time or B) 1-3 minutes late to just about everything. Maybe I’ll write a post about this in the future.

(but wised up and decided to treat the fools like me who run)

How politely ambiguous!

Of everything that happened on February 20th, I’m proudest of what happened next

Gregory Hays has done the best translated version I’ve read of Meditations