What Toddlers Can Teach Us #4

Of all the ways parenting changes the brain, I didn’t expect it to have me questioning myself so often. Of course, there are the constant, unrelenting, dour, everyday insecurities of having absolutely no idea what you are doing yet also trying to be an example for a tiny human.

But there are also questions of why, how, and if, XYZ behavior leads to XYZ type of adult.

Read: self-scrutiny, self-criticism, curiosity how baby J → adult J

Lately, what’s been running circles around my mind has come in the form of leche—milk. Spilt, chugged, refused, thrown, dribbled, kicked, spoiled, dumped, frozen, licked, or whatever else a very tiny human does with said milk.

To be direct, the question is why toddlers love the word no and rarely say the word yes.

“So you don’t want the leche1?” I say to him

“No. No, no, no, no, no, no, no,” he replies, as the lime green sippy cup goes flying across the kitchen, as I make a leap and, yes, harking back to my glory tight end days for the East Greenwich Avengers2—catch the green milk meteor.

“We don’t throw,” I say to him (yet will of course, five minutes later, encourage him to throw a ball my way). “When you don’t want something, you leave it on the table.”

He looks at me like I am a strange, strange man—like my hair is too long and growing sideways. Like I have just spoken in great indecipherable sonnets of olde english.

Then, he shakes his head—furiously. Flails redly. Swipes his hands across the table, through his dinner, sending cubes of cheese and smashed strawberries and Cheerios to the hardwood.

The hounds arrive. He laughs like a tiny little supervillain as Pepper gobbles her winnings.

Then he begins to yowl.

“MORE. MORE. MORE. More, more, more moooooore.”

I open up the refrigerator and read off every feasible item—anything he has ever, at any time, desired.

“Pouch? Apple? Pear? Grapes? Hammy? Chicken? Blueberries? Hommus? Yogurt? Meatballs? Mac?”

“No, no, no, no, no, no.”

“More!” he howls and holds his arms out. His face goes a shade more red.

The milk is leaking on the hardwood. I pick it up and open the fridge and as I set it down on the shelf I hear—

“More leche?”

I wish I could have seen my reaction as I picked up said milk and delivered it to the boss himself, my face must have been some rare mixture of desperate furious amused satisfied-ish comic relief.

“You want the leche now?” I ask.

He reaches. I put the milk in his hands

He looks me straight in the eye.

“No” he meeps, shakes his head.

Then, smirkingly, maybe even knowingly, slurps the milk in his hand.

In the moment, I don’t wonder whether or not he knows what “no” means—it’s whether he knows he is messing with me or not.

That he says “no,” then proceeds to slug his milk might be him not knowing the word’s meaning, but I think that’s underestimating him—and all the cunning little toddlers. It seems to me that tiny humans are much, much more intelligent than we give them credit for. He knew what he was doing—that the incongruence between his volley of “nonononono” followed by a thirsty milk hootenanny would draw a reaction from me. Capture my attention. And the capturing of your protector’s attention is, no matter what year it is, a genius level survival instinct.

I digress.

Here are some books I recommend for August.

(If you’re interested in some research on the above, skip to the end of this post.)

Books I Recommend for August 2025 📚

SMOKEBIRDS BY DANIEL BREYER

I was lucky enough to get an advance copy of this book, and knew after reading that it was going to catch fire, pun intended. Smokebirds has been described as “climate fiction” and even “speculative fiction” because it is set in a near future where, once every year, California is on fire. Not the destructive, tragic sorts of fire we see today, but rather an all consuming, life reforming “fire season” that’s caused the state’s institutions to establish all sorts of air purification measures and technologies.

In short, during fire season, you walk outside and the smoke is in everything, everywhere. You wear a mask all the time, and it has special filtration.

OR , if you are wealthy, you spend the season in Hawaii.

Of course this review is entirely subjective. Dan is one of my closest friends; I find him hilarious, intellectually fresh, interesting, original.

If you’ve listened to Good Scribes Only, you know him well.

Breyer’s debut novel is not perfect but, in a world where literary fiction3 is dying a slow, quiet death, DB shows us that there is still at least a scrap of hope.

During the book launch, which was a lovely and inspiring event (win for books!), I described the novel as a cross between George Saunders, Jonathan Franzen, and Dave Eggers. It’s a black comedy that’s dangerously self aware, showing extreme composure and control on the page—a combo I do not have and find hard to come by.

Here’s the link to watch our conversation from Dan’s book launch at Green Apple Books in San Francisco.

Consolations by David Whyte

This was my second time reading, and it’s a book I’ll likely revisit again and again. I’ve raved about Whyte here plenty; he strikes me as the only writer in Mary Oliver’s orbit when it comes to prose and poetry. There’s something particularly ripe about the Consolations book project. Whyte is a poet, but this is not poetry per se; each passage (a page or two at most) takes an everyday word—memory, nostalgia, shadow, silence—and turns it over, makes you consider it in a new way.

GROUND

is what lies beneath our feet. It is the place where we already stand; a state of recognition, the place or the circumstances to which we belong whether we wish to or not. It is what holds and supports us, but also what we do not want to be true; it is what challenges us, physically or psychologically, irrespective of our hoped for needs. It is the living, underlying foundation that tells us what we are, where we are, what season we are in and what, no matter what we wish in the abstract, is about to happen in our body, in the world or in the conversation between the two.

The best news: I just found out there’s a Consolations II (which I just now ordered.)

Horseman, Pass By - Larry McMurtry

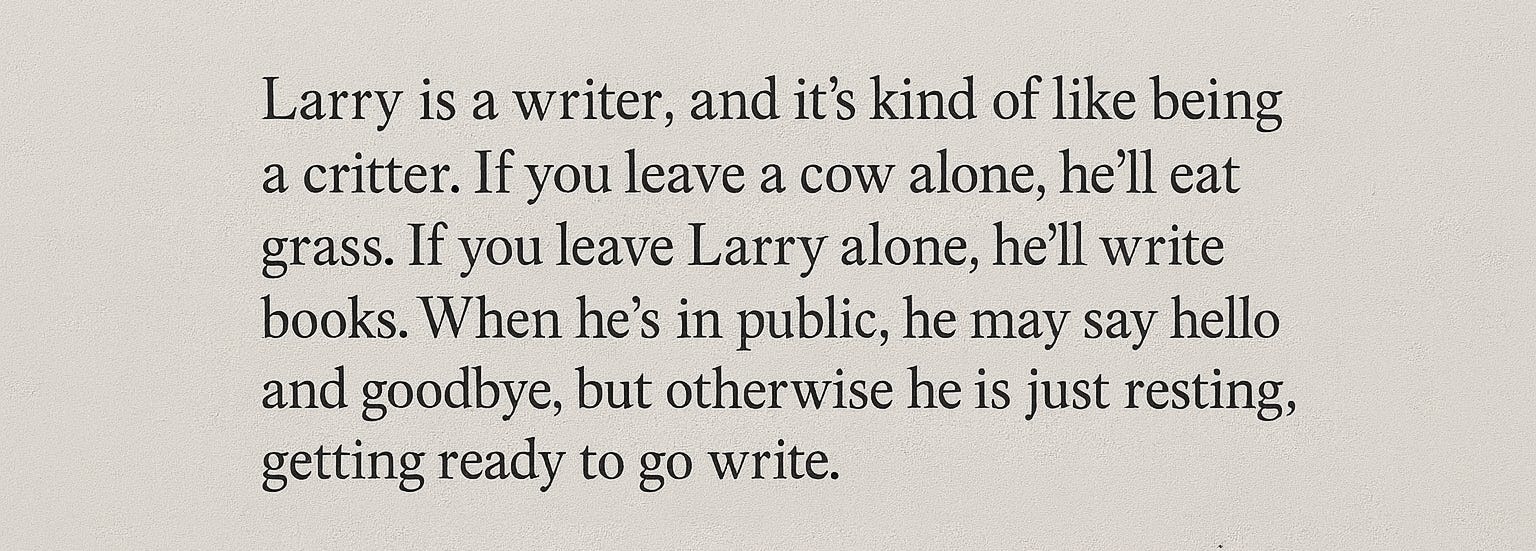

I hadn’t heard of Larry McMurtry until a year or two ago, and it wasn’t even from a Texan. McMurtry, who helped write the Brokeback Mountain screenplay, is probably the most decorated writer of contemporary High Western4 fiction. He runs semi-parallel to writers like James Michener and Cormac McCarthy, albeit on a slightly different track. Where McCarthy is dark and existential, McMurtry is nostalgic, wide open, bittersweet. I don’t have enough reading experience on McMurtry to say much more than I enjoyed this book a lot and plan to read more of him in the near future.

Instead, here’s a short quote from his biographer that I find heroic:

Horseman, Pass By is McMurtry’s first novel, telling the stories of Homer Bannon—an old-time cattleman who is emblematic of frontier values. Hud, his unruly stepson. and Lonnie—Homer’s young grandson who is both drawn to his grandfather’s strong character and to Hud’s materialist hedonism. The book was a bit of a sensation

when first published in 1961: lauded for its bluntly realistic rendition of a struggling, changing West following World War II. He was one of the first to capture that environment so unsentimentally and without bias, employing provocative characters and timeless themes, and telling it all in a sort of Hi-Resolution-Country-Prose. Utterly sad, utterly lovely.

Listen to this one on Good Scribes Only.

Golden Son by Pierce Brown

I am not too proud to say that what Pierce Brown has done is both admirable and rare. By thirty, he had written three NYT best selling Sci-Fi books, called the Red Rising Saga. They aren’t popcorn fiction—which of course has its place in the world but isn’t what I plan to write. They are far more literary, and are derived from important and classic literary works. Characters with namesakes like “Lysander,” “Nero,” and “Octavia”—mapped over timeless stories of war and politics and betrayal.

Darrow, the saga’s main character is a “Red”—a member of the lowest caste in the color-coded society of the future. Like all Reds, he works constantly, in dangerous conditions, under the guise of making the surface of Mars livable for future generations.

When Darrow discovers the truth—that there are vast cities and sprawling parks spread across the planet, and that he and his kind are nothing more than slaves—the story takes a turn toward revolution and justice. Not to mention a plot to infiltrate the legendary “Gold” Institute, where the next generation of humanity's overlords struggle for power. It’s certainly not a perfect book and series, it’s absolutely worth the read.

Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks by Yuval Noah Harari

Yuval Noah Harari is another writer I have read and re-read, and written about. He’s also been the subject of some less spotlight in recent years—whether rightly so is to be seen. The argument against Harari is, in the words of philosopher John Gray “an intellectually lightweight form of pop philosophy, history, and futurology, full of sweeping generalizations and speculative claims dressed up as fact.” Respectfully, I think that’s a bit of shade from a person who wishes his ideas were as digestible and widely read as YNH.

Nexus surprised me. It wasn’t as widely featured on podcasts or book lists, and so I expected it to be underwhelming. What I should know by now is that attention only sometimes correlates to quality. As Harari is wont to do, the book takes a long view of history, ushering the reader from the Stone Age to the Bible, to early modern witch-hunts, to Stalinism, Nazism, and today’s resurgence of populism. Harari provokes considerations about the prohibitively complex entanglement between information and truth, bureaucracy and mythology, wisdom and power. He uses history to illustrate how some societies and political systems have wielded information to achieve their goals—for good and for ill. As usual, he closes the book with the urgent questions we face as Large Language Models like ChatGPT, self driving cars, and other non-human intelligence loom large.

Information, he argues, is neither the raw truth, nor a weapon. It is a tool to find the middle ground we humans are so gifted at evading.

Other Reads Worth Mentioning:

Onyx Storm by Rebecca Yarros

The Sense of an Ending by Julian Baker

The Andromeda Strain by Michael Crichton

House Made of Dawn by N Scott Momaday

To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf

Angle of Repose by Wallace Stegner

Be Love Now by Ram Dass

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

All the King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren

Scientific Advertising by Claude Hopkins

No-Predominance in Toddlers

Research says that “No-Predominance” is predictably developmental. Kids say “no” first for an obvious reason—it’s easier to pronounce—but also because it’s more useful.

The developmental psychologist Gopnik calls it “practice for agency,” because “NONONO” helps a tiny human exert agency in a world where they have very little control. The child’s identity is wrapped around what they refuse.

For many of us, however, identity is wrapped around what we choose—what we say yes to. Somewhere along the way, we trade no in for yes.

But when?

Likely it’s a slow, plodding, gradual process.

I have no scientific evidence whether this is environmental or genetic or downright incorrect, but it seems like as the human brain matures it learns to say yes, and to desire more. So, over the years, “yes” and desire are intertwined. “No,” on the other hand, at the most fundamental, becomes entwined with less. And less—it seems—may be tied to finding any sort of peace.

Does this mean I am going to stop being an ambitious writer and curious person? Am I going to give up all of the hobbies I’ve grown accustomed to over the years?

Certainly not.

What it does mean is that I might do a better job of modulating my Yes/No-altimeter. Might use those the relentless NoNoNoNoNo-ing as a reminder that parenting is as much about being taught as it is about teaching.

Anyway. Some great books next month.

See you,

— Jeremy✌️

His daycare refers to milk as leche and water as agua, which we happily continued

#88 was always open

Apologies for the jargon. Literary fiction = Books that are not fantasy, sci-fi, mystery, thriller, etc…

High Western, meaning more literary than a classic run-and-gun cowboy story.